When the Distributor Sales Culture Met E-Commerce

Low-cost alternatives to full-service distribution at hand and at work

Scott Benfield

The predictions of e-commerce as a way of doing business and as a possible threat to existing full-service distribution are, day by day, becoming increasingly accurate. B2B buyers are more and more voicing their preference for an e-commerce solution for commodity purchases. In a recent Forrester survey of B2B buyers, the prediction is that by 2020 there will be one million fewer sellers in B2B ranks as buyers simply don’t need them.1 Our work, over the past decade, has repeatedly followed the reduction of cost in merchant wholesaler channels including the effects of consolidation, technology, and the reduction in operating costs of the current platform.2

The predictions of e-commerce as a way of doing business and as a possible threat to existing full-service distribution are, day by day, becoming increasingly accurate. B2B buyers are more and more voicing their preference for an e-commerce solution for commodity purchases. In a recent Forrester survey of B2B buyers, the prediction is that by 2020 there will be one million fewer sellers in B2B ranks as buyers simply don’t need them.1 Our work, over the past decade, has repeatedly followed the reduction of cost in merchant wholesaler channels including the effects of consolidation, technology, and the reduction in operating costs of the current platform.2

The question we attempt to answer is what does the merchant wholesaler need to do to compete with well-financed e-commerce platforms that are challenging the commodity sale with a reduced cost platform? If our predictions are correct, the competitive challenge will elicit significant changes in the existing business. Those companies where adherence to a sales culture are strongest, will suffer the most.

Second vs. First Generation Capabilities

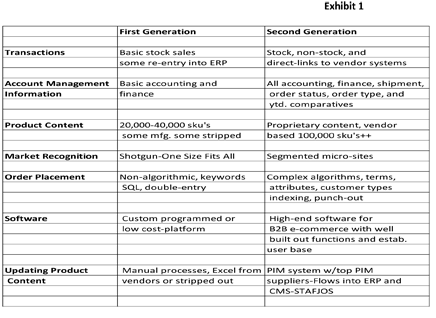

From the late 1990s until the Great Recession, e-commerce capabilities were, for most merchant wholesalers, approximately the same. Many firms had a basic system, often a custom-programmed platform that processed simple transactions, gave access to 20,000 to 40,000 products, and allowed a basic review of the order as it matriculated through the organization. As the Great Recession ended, however, there began a sharp difference in technological capability in online commerce that favored the larger firm with deep pockets. SKU counts sharply increased, with leading firms having one million or more SKUs online. Procurement punch-out, a technology that allowed the end-user to enter the order once and manage purchase access, became available as did PIM (Product Information Management) software which kept million SKU databases current and accurate. Independent software companies specializing in B2B e-commerce also appeared and offered a far superior product than was available a decade earlier. Finally, search technology improved with software that allowed multiple search parameters far beyond that of traditional keywords. The firms that secured these technologies paid dearly for them, often into the millions and tens of millions of dollars, depending on the size and complexity of their offerings.

Wholesalers with these technologies are second-generation e-commerce firms. They invested, often as contrarians, and plowed capital into the new technology. Their intent was clear; to develop a technological superiority in breadth of product, search capability, and customer options. Today, firms with second generation technologies have organic growth that is often twice that of their competition. The difference in first- and second-generation technologies can be seen in Exhibit 1. On almost all levels, the second-generation technology, and usefulness to the customer, is today’s expectation. Our field work and research on wholesalers with first-generation technologies find that most of them transact less than 5% of their sales online. For all intents and purposes, they serve outliers, customers who cannot find what they need elsewhere and have to buy from their site. Firms with second-generation platforms are 20% or less of all distributors and are growing at the expense of their less technologically advanced competitors.3 They represent 80% of all online sales in traditional distribution markets.

As second-generation technologies became the norm, their host companies used the technology to develop a pincer movement on the served market, one that, if history is a guide, will be a significant threat to the rank and file distributors who number in the thousands.

Retailing history and lessons for wholesalers

In the early 1960s, there were some 316 full-line department stores in North America. They covered a full range of goods; often from appliances to fashion and much in between. The problem with the business model, as it was later learned, is that the sprawling, full-service approach was costly and inefficient. Trying to service all customers with most things was a pending recipe for going out of business. In and around this time, low-cost retailers (think Wal-Mart, Target, etc.) appealing to economic buyers or out-of-the-way geographies, began to emerge. They attacked the bulk purchases for the cost conscious with low-operating cost platforms and gave a substantial portion of the savings back as a price decrease to the customer. The full-service retailer was in a quandary. They could not sustain a price competition forever as their operating model was too expensive; they could move to higher value merchandise, but the market for this was limited in size. Eventually, they were disrupted4 where, over the past 50 years, a handful of full-service department stores dominate the U.S. economy. Hundreds of their brethren died out to lower cost competition.

Merchant wholesaling has been well-established since the Civil War. As the B2B economy expanded, the need to get parts and pieces to market exploded. The core value proposition where goods from different vendors were assembled in a transaction that met an application need and whose margin dollars exceed the fulfillment cost has been resilient for three or more generations. Along with the resilience of the basic value proposition came a culture of inside and outside sales forces; the latter covered geographic territories and typically cost 3% to 5% of sales while the former cost 2% to 4% of sales. But technology has allowed a new breed of competitor by carving up the basic value proposition of wholesaling and the parallels with retailers of old are worth noting.

Busting apart the transaction or away with the A’s

Inventory classifications in merchant distribution include A items - 70% or more of sales and mostly high-volume commodities, B items - 20% or so of sales and some commodities and some not, and C & D items and other categories titled non-stock or order-as-needed. Wholesaling works because A items are paired with other categories to solve an application issue. But A items are well-known commodities and don’t need much, if any, sales support. Customers often know more about them than the wholesalers that sell them. The problem is that the existing model of distribution has lumped a lot of costs into supporting A items including sales costs, local branches and supporting expenses. But second-generation e-commerce allows the customer to order A items without expensive support mechanisms that don’t add value to the goods. The traditional transaction and its resilient value proposition are literally being busted apart. There’s no need to pay 5% or so for sales support and other additional expenses if one doesn’t need to; the opportunity to reduce price and offer a more convenient service is a reality and the economic advantage is real. And, as search technology and SKU databases grow, the A item migrates to the B, C, D and non-stock categories. As long as the product is not altered by the distributor, the customer can search for it, find it and buy it less expensively online.

To support our research, we point to tangible “low-cost” sites that strip out many of the redundant support costs and/or change the channel dynamics to give the customer a better value proposition. First, leading e-commerce wholesalers Grainger and MSC Industrial have low-cost entries Zoro Tools (www.zoro.com) and Enco (www.use-enco.com). These sites openly advertise low prices and ostensibly are branded versions of their parent companies’ second-generation platforms. Another entrant of interest in the PHCP sector is HVACstores.com and their online platform ACWholesalers.com. The firm sells condensing units and accessories direct to the public and bypasses the well-established but sclerotic wholesaler/dealer network. The company is on the INC list of fastest growing firms. Its entrance into the market is a low-price or “retail sales at wholesale prices.”

The challenge to full-service distributors, chock full of geographic sellers and branches, is like that of the full-line department stores of old. Their business model is being carved apart by technology that challenges the core value proposition. If they react to the low price competition, they literally bleed profit. If they move to services and assemblies, they pursue higher value markets but will shrink in size. If they leave the new models alone, they will lose customers at an increasing rate. The disruption is at hand.

What are the options for the sales culture?

The viable options for existing distribution are limited. In the past, we’ve encouraged moving further into the value chain into assemblies and services but these markets are smaller in size and the competition is increasing as the rank and file wholesalers feel the squeeze of the new, low-cost models. The vaunted acquisitive model is in trouble. It takes cost of the back door functions and leverages consolidated purchase volume to the vendor base. But acquisition and consolidating operations is no match for a stripped-down, sleek and organic growth model like Zoro, Enco, etc. Acquisitive strategies become unwieldy over time, the culture differences pile up and work against efficiencies. Finally, the popular subjects of solution selling and pricing are waning. The solution selling mantra only goes so far when the customer buys the A items from someone else and pricing, eventually, gets found out (especially with online comparisons) which accelerates the customer’s move to the low-cost, online competitor.

The sales culture is, for all intents and purposes, in trouble. Hence, Forrester Research’s pronouncement of 1 million jobs lost is not a surprise. To compete, traditional wholesalers will need to pony up the capital for second-generation technology. But this is more difficult than it looks. Firms successful in e-commerce have strong marketing functions before they move online. Markets are segmented, product managers develop product taxonomies, service platforms are scrutinized and streamlined, and the supply chain undergoes Business Process Management work in addition to securing second-generation functionality. In short, good marketing and supply chain management is a prerequisite for going online. We find many wholesalers have a marketing function but it is poorly staffed and not strategic. Where marketing is strong, online presence is, generally, good. Where marketing is weak, online transformation, even with current technology, is difficult.

What Remains

The transformation of distribution will take time. Technology costs will likely come down and there will be distributors that thrive with the changes. Sales forces will grow smaller and more specialized. But they will be integral to growth of new and more lucrative value streams; cost out strategies don’t last forever. Staying the course with the old model, however, only gets less where there was once more. It is a sure bet for “more of the less stuff.” We encourage wholesalers to begin the transformation sooner rather than later. The technology to disrupt the supply chain is functional and works quite well. Further advances in technology are likely to be less disruptive than they have been from first- to second-generation systems. Selling one’s way out of the problem — at least in an undifferentiated mode — is likely to work against success.

Scott Benfield is a supply chain consultant for B2B markets. He is the author of six books, numerous research projects, and trade magazine articles. He has been quoted in Forbes and The Financial Times and consulted with Fortune-rated companies and mid-range firms in North America. He can be reached at scott@benfieldconsulting.com, (630) 428-9311, and his site is www.benfieldconsulting.com.

1 See Forrester announcement on April 13, 2015 at: https://www.forrester.com/One+Million+B2B+Sales+Jobs+Eliminated+By+2020/-/E-PRE7784

2 Benfield, S. Griffith, S. “Battle for Capacity,” White Paper at: http://benfieldconsulting.com/uploads/battleforcapacityandstrategyby20207.pdf

3 Benfield, S. “Channel Conflict E-Style, at: http://www.industrialsupplymagazine.com/pages/Article---Channel-conflict-e-style.php

4 Bennett, D. “Clayton Christensen Responds…”, Bloomberg Daily, June 20, 2014.

We feel the e-commerce is evolving very rapidly for distributors, supply warehouses and B2B customers. It is just a matter of time when online sale will represent large portion of business, if not all of it.

We feel the e-commerce is evolving very rapidly for distributors, supply warehouses and B2B customers. It is just a matter of time when online sale will represent large portion of business, if not all of it.