The Value Decade: New Operating Rules for Durable Goods Distributors

by Scott Benfield

Durable goods wholesale distribution is a $2 trillion sales entity of the U.S. economy. This series will demonstrate that the century old model is under significant stress from technology, globalization of supply and cultural impediments and is in danger of losing sales to more efficient models of business. Due to its size, wholesale distribution will be a significant contributor to the U.S. GDP, however, the structure of wholesale entities will need to adapt to keep pace with the growth in durable goods consumption.

Part One: New Research for New Times

For all intents and purposes, wholesale distribution is an industry with a modicum of research. In years past, most research was done by associations but because of consolidation and the recession, research budgets have largely dried up. A few of the larger industry vertical associations and national associations still sponsor investigative review but there is little outside empirical study done on the industry. In the first half of 2012, however, a spate of research appeared in several prominent publications outside the industry. Combined with research from industry consultants, the message for wholesalers is that the industry, in the post-recession economy, is changing rapidly and not necessarily favorably for established cultures and ingrained predispositions; unexamined and unchallenged experience may be a detriment.

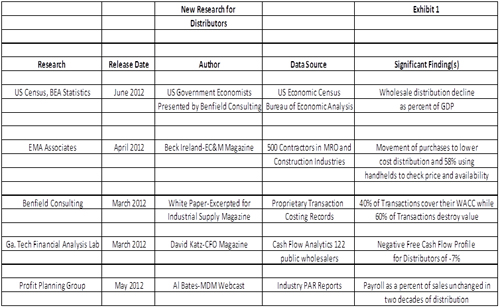

We have listed the new research and its portent, as we interpret each study, in Exhibit 1. In the Exhibit, we have listed the research along with the release date, author, data source, and significant finding(s). The first three entries come from outside the distribution industry. Much of the intra-industry research tends to confirm the way things are done as the right way to do them. It suffers from Existence Bias which is the assumption that “…mere existence leads to assumptions of goodness: the status quo is seen as good, right…and desirable.” It is notable that three critical pieces of research from outside the industry are done in a short time period and all point to significant changes in the existing operating model of wholesale distributors.

The first noted bit of research comes from two arms of the U.S. Government including the U.S. Census (Merchant Wholesale Trade Sales) and the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The two data sets are compiled by economists employed by the U.S. Government and are publicly available. Using both data sets, we compared durable goods wholesale distribution sales, as a percent of the Current Dollar GDP, from 1995 to 2010. In 1995, durable goods distribution sales were $1.14 trillion of a $7.41 trillion GDP or 19.7%. By 2010, sales were $1.87 trillion or 13.7% of a $14.75 trillion GDP. During the 15 year period, durable goods distribution sales grew at an approximately 2.6% per annum rate, however, the GDP grew at a 3.33% per annum rate. Over the period, durable goods distribution sales declined 30% as a percentage of the GDP.

From the data, two things are obvious: First, durable goods distribution is slowing in growth relative to the GDP. This could be either because durable goods distribution is losing sales to other channels, the GDP is growing in other sectors than durable goods, or both. Second, declining channels, over time, become more price competitive as existing players battle it out for the remaining share. In general, cost becomes key as overcapacity is reduced and products become commoditized; consolidation is one method of getting capacity down and cost out.

From the data, two things are obvious: First, durable goods distribution is slowing in growth relative to the GDP. This could be either because durable goods distribution is losing sales to other channels, the GDP is growing in other sectors than durable goods, or both. Second, declining channels, over time, become more price competitive as existing players battle it out for the remaining share. In general, cost becomes key as overcapacity is reduced and products become commoditized; consolidation is one method of getting capacity down and cost out.

Lower cost channels win out in slow growth markets. One theory is that retail channels, including big box stores, e-commerce retailers of durable goods, and other non-wholesale entities have entered into the distribution space. During the same 15 year period of the wholesaler decline, retail sales grew from $2.4 trillion in 1995 to $4.3 trillion by 2010 for a slightly better than 3% per annum growth rate. The migration of product sales from one channel to another is common. This is typically the result of channel structures that give a better value proposition from a lower cost basis of operation. Typically, lower cost channels reduce services or streamline operations with technology and give a lower price point as was detailed in recent research of contractors working in maintenance and new construction markets.

In April of 2012, a research project involving the purchasing behavior of 500 contractors was released. Done by EMA Associates of Syracuse, the survey found that contractors were picking up more supplies from big box stores (Home Depot and Lowes) because of better availability and lower price points. This was especially true in tools and everyday A&B items. Further personal surveys found that contractors were buying key items from retail channels as they were less expensive than from traditional wholesalers. Big box stores don’t have outside sellers and leagues of inside sellers like traditional wholesalers. Traditionally, this group of services costs 35% to 50% of total distribution operating expenses. Too, big box stores often don’t deliver goods which costs upward of 2% of sales. If contractors found a decreasing value in sales and delivery services, it would give Big Box stores a considerable cost advantage. Additionally, the survey found that where contractors had wireless hand-held devices, 58% used them to compare product specifications and check price and availability. The use of technology favors retailers as they are typically more advanced in their design and usage of e-commerce. Too, technology and the availability of price comparisons has been shown to drive down price increases which further compresses operating margins and moves the focus to cost reduction to maintain satisfactory returns.

The RMA survey points to a shift in buying preferences from traditional distributors to big box stores and most likely because of reduced price points. Again, price points are reduced because of limited service offerings and a lead in e-commerce technology. We mentioned the survey to several large wholesalers but the results were dismissed as their view of contractors who visit big-box stores were small and not “legitimate” as they are doing work outside of their regular employ. The follow up personal surveys and size of the respondent base, however, disagrees with their assessment. In essence, many legitimate contractors are increasingly purchasing from non-wholesale entities and this is expected to continue. Too, we believe other retail channels including Amazon and Ebay will take business away from traditional wholesale channels but this effect is not quantified. The retail building products channel, from U.S. Economic Census, grew at an approximate 3% rate during the 1995 to 2010 period or four-tenths of a percent per annum more than durable goods distribution. The U.S. Government Statistics on durable goods distribution and the RMA research points to a general decline in wholesale distribution as a percent of the GDP and a rise in alternate channels. The overall effect of alternate channels on wholesaler sales is unknown, however, the information suggests they are making inroads because of a lessened service platform at lower price point(s) and employ a greater use of technology to support their cost advantage.

The High Cost Service Provider in a Value Conscious Market

Much has been written about value added and creating value for customers by helping them eliminate redundant processing costs in the supply chain. For all intents and purposes, value is a construct and “value added” can easily create a culture where over-investment in services is justified without requisite financial analyses. The subjects of integrated supply, total cost of ownership, and gain-sharing have been part of distributor to customer relationships for two decades. Many distributors have created and mapped sales processes dedicated to removing redundancies in supply chains with larger customers. However, the vast majority of customers are served with little in the way of service differentiation; the result being that many customers are given service(s) that they can’t afford or simply don’t want. The problem with this dynamic, in a world of instant price and availability, is that a very few customers support the vast majority. Our work in measuring the financial value of customers finds that 40% of customers have a return greater than the weighted average cost of capital, 40% of customers have a negative profit, and 20% have a positive return but below the weighted average cost of capital. As price, in a world of perfect information, is less of a solution for low return/high cost to serve customers, wholesalers will need to structure their operating capacity with greater accuracy differentiating amongst customers who want full service and those who don’t. We view the dexterity in usage of operating capacity to be the singular most influential and important variable for wholesaler financial success in the next decade. Our rationale is supported by research that, again, emerged in the first half of 2012.

In March, CFO Magazine released a research project done by the Ga. Tech Financial Lab on the Free Cash Profile(FCP) of Wholesalers. The Ga. Tech Financial Lab is one of the leading forensic accounting programs in the country and researched 122 public wholesalers on their ability to generate free cash flow and fund growth. Free cash flow is, basically, the operating profit of the firm less taxes and less deductions in capital investment. It measures the firm’s ability to fund growth and is the foundation for shareholder value with the accepted formula of Value=Free Cash Flow/Weighted Average Cost of Capital-Growth. The Ga. Tech research found that Wholesalers were 39th. of 44 industries in their free cash flow profile(s) with a -7% score. Furthermore, the study found that nearly half of wholesalers borrowed money to fund growth as they were not earning sufficient returns on existing investments. We view this dynamic as a downward spiral where wholesalers literally borrow money to lose money. From the study, “…a company with a negative FCP might be able to generate free cash flow: it just better not try to grow.”

A negative free cash flow profile creates numerous problems including decreased ability to react to low cost competition and short-term solutions such as indiscriminately raising prices, stumping for rebate dollars, reduction in service quality through hacking expenses, and layoffs. Anecdotally, we’ve seen a rise in these tactics with the unsurprising result of limited increases in operating income followed by customer defections. We believe the core cause of the negative free cash flow profile is an entrenched service model that cannot and does not discriminate in serving different customers and segments with differing service platforms. Too, the Robin Hood strategy of borrowing from the 40% (Rich) sales and marketing “investments” that generate sustainable profits to pay for the 60% (Poor) is being exploited by lower cost channels; hence the slow-down in growth for traditional durable goods wholesalers. The problem is not simply poor productivity but an undifferentiated and poor use of capital to identify and fund growth that covers the cost of deployed capital. This is exacerbated by financial accounting which does little, in a supply chain business, to track the financial value produced by discrete marketing and sales investments. Our hypothesis on poor deployment of capital to labor was recently echoed by an industry insider, Al Bates of Profit Planning Group. In a May 2012 Webinar for Modern Distribution Management, Al commented that for the past two decades, he has seen little or no improvement in the ratio of payroll cost to sales for wholesale distributors. This is significant as salaries and wages typically comprise 60% or more of distributor operating expenses and are a powerful variable in productivity improvement.

In the long run, mature industries compete on productivity and don’t simply rely on new product and service development as they do in the growth stages of the industry life cycle. Typically, firms reduce investment in mature products and services and people who produce them and move labor to newer offerings. Primarily because of a financial accounting headset which draws a linear relationship between margin percent and bottom line profits, wholesalers seem stuck in a branch centric and service intensive model where there are significant numbers of branches, branch managers, outside sellers and inside sellers. We will challenge this headset in upcoming installments in the series and show that, to maximize value, wholesalers must move away from heuristics gleaned from the income statement.

The traditional service platform is expensive and in an era where GDP is low, technology allows for instantaneous information on price and availability, e-commerce disintermediates sales capacity from placing an order, and global manufacturing creates product cost deflation, the insistence of a full-service complement, without understanding if the service(s) create financial value, is dangerous. We believe that the high growth GDP from 1995 through 2007 of 5.4% masked labor cost issues and problems from a stagnant service model surfaced as the U.S. GDP has grown at a much reduced (2%) rate since 2008. Most long range forecasts have the U.S. GDP growing in the 2% to 2.5% range for the rest of the decade. Hence, we believe that wholesalers will have to fundamentally and substantially address the deployment of labor and challenge the full service model to secure a positive free cash flow and fund growth.

The Value Decade

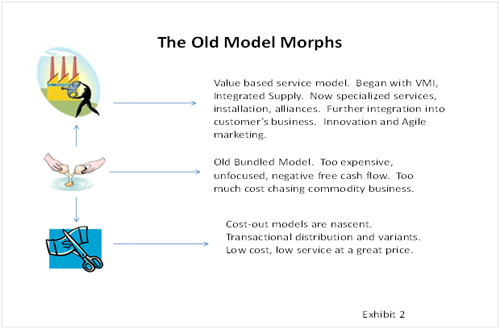

Creating and adding unique services has had a long, successful run for wholesalers and without significant challenge from other supply chain models. In most instances, wholesalers could add services, specific to the customer, and roll them into the product price. Some wholesalers have created fee based services, however, this effort is small in relation to the bundled-basic service model. The problem in bundling is that the greater the service variation, the greater the cost and the greater the likelihood that a particular customer or group of customers bears cost(s) for services they do not receive or want. The current research points to the basic-service bundled model being challenged with different value platforms from the use of better marketing into unique services, technology, import products, and a better understanding of how service costs impact product price. In Exhibit 2, we see an illustration of what is happening with traditional distribution. The basic service bundled model is like an egg that is being broken apart. Replacing the bundled model are the integrated services model and the stripped out cost model. We see MRO services moving beyond integrated supply where wholesalers enter into retrofit, monitoring, and perhaps even installation services. These capabilities will likely come more from alliances than development of core capabilities. Too, we see growing evidence of cost-out or Transactional models where the best global price is combined with streamlined basic service models that reduce cost 20% to 30% over current offerings.

Both of the new models provide a different but better value proposition than the traditional model. Much depends on the customer’s demands and whether they have a need of specialized services and wish to outsource them or are satisfied in staffing maintenance and ordering capabilities and simply want a good product at a great price. In the future, wholesalers will not only need to understand how the bundled-basic service model can be disintermediated, but how the culture of the bundled-service model will need to give customers a service menu with varying prices on a variety of service choices.

Over time, service value migrates to a more efficient platform with more choices on the price-service spectrum. We explore this migration in the next installment, how it has created a culture with significant impediments to change, and what wholesalers will need to do to better compete in a decade where differing value propositions with varying prices are sought by customers.

Over time, service value migrates to a more efficient platform with more choices on the price-service spectrum. We explore this migration in the next installment, how it has created a culture with significant impediments to change, and what wholesalers will need to do to better compete in a decade where differing value propositions with varying prices are sought by customers.

Scott Benfield is a consultant for B2B channels. His practice, Benfield Consulting, is located in Chicago and Scott can be reached at Scott@BenfieldConsulting.com or (630) 428-9311. This series is taken from the consultancy’s new book: Building Value: Driving Wholesaler Returns Through Strategic and Tactical Investment and can be ordered at: http://www.benfieldconsulting.com/Buy_Now.html.

Scott Benfield is a consultant for B2B channels. His practice, Benfield Consulting, is located in Chicago and Scott can be reached at Scott@BenfieldConsulting.com or (630) 428-9311. This series is taken from the consultancy’s new book: Building Value: Driving Wholesaler Returns Through Strategic and Tactical Investment and can be ordered at: http://www.benfieldconsulting.com/Buy_Now.html.