Make sales training work

by Chuck Holmes

The complaint usually goes something like this: We did the sales training. Took the whole sales force out of the field. Paid somebody to come in and do it. And nothing happened. How’s that?

The short answer is probably that you can give somebody the skills to do something, but that doesn’t mean that they’ll use them. Getting people to use the skills they have is not a training problem.

Or, it could be that the training administered was not specific to the problem identified. The salespeople had new skills, but they didn’t really impact the problem.

In this article we’ll look at three steps that will, if properly taken, make your sales training more effective. The three steps are:

1) Prioritize your training

2) Make sure you use all of your tools

3) Measure the ROI

In the accompanying example, a fictional sales manager demonstrates how these steps are executed. This is to demonstrate the process (if you do it, your lists and actions will be different).

Prioritize your training

Actually, there’s no such thing as “Sales Training.” Training is designed to teach somebody how to do something, and sales are a result rather than a skill. Rather, we teach salespeople to do specific things, such as prospecting, pricing, negotiating, problem solving and — to stretch the term — product knowledge.

There is, of course, a group of skills that we call “basic sales skills.” Some salespeople have been through two or three courses of these.

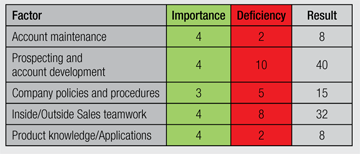

To get the most from your training, you need to start with the group of skills that will provide the greatest return on your training investment if you can get the salespeople to use them. One way to determine that is to make a list of all the things your salespeople should be doing and rank them using a two-factor index: importance and deficiency. In other words, what’s the most important set of skills that has the most room for improvement.

We use a 1 to 4 scale for importance, with 1 being the least important and 4 being the most, and a 1 to 10 scale for deficiency, with 1 being absolute competence and 10 being salespeople without a clue. When you’ve ranked each of the identified areas, simply multiply the two factors and sort them from the highest to the lowest. Your training should start at the top of the list (subject to possible exceptions identified in the next section).

Use all of your tools

When you’ve identified the priority areas, the first thing you should do is make sure that it’s a training issue.

Generally, there are three reasons, either singularly or in combinations, why your salespeople don’t do what you want them to do. They are:

1) I can’t

2) I won’t

3) I don’t know how

The first of these reasons has to do with systemic problems in the company. If, for instance, you’ve asked your salespeople to spend the bulk of their time on accounts with high growth potential but keep sending them to core accounts — the big ones that pay the bills — you have a systemic problem. The salespeople can’t comply even if they want to. Systemic problems should be removed before efforts are made to change behaviors.

The second reason means exactly what it says. The salesperson either consciously or unconsciously refuses to do what you want. One of the few contracts that I’ve ever refused was to teach a company’s salespeople to do meaningful sales reports. I knew that I could teach them everything they needed to know about sales reports in about an hour, but a lot of them still wouldn’t turn them in.

The third reason deals with training issues. The salespeople would do what you wanted, and there are no external reasons why they shouldn’t, but they don’t have the skills. This is where training can make a difference.

In order for training to be effective, you have to eliminate systemic problems and provide a motivation that makes the salesperson want to use the new skills. Often this has to do with compensation, but there are other ways of motivating salespeople.

In the example above — the call reports — the problem is that salespeople generally don’t like them. They don’t see why they should devote an hour or more a week to an activity that doesn’t contribute directly to their situation and providing information to management isn’t one of their priorities. There are a number of ways that you can make submitting call reports more important to the salesperson (e.g., making it part of their compensation, making it part of qualification for advanced training, or making it a factor in company-wide recognition). In any event, it has to be something that’s important to the salesperson, rather than just to the company.

Measure the ROI

Return on investment is a big thing in most companies. We spend money to make money, but we want to make sure 1) that the money is well spent and 2) how much we can expect. Somehow, we don’t do that with training, or if we do, it has to do with relative ROI between delivery systems. However, getting a usefully accurate ROI for any training is not that difficult. It involves answering three questions:

1) Why am I doing this?

2) What good thing will happen if it’s successful?

3) How do I measure the result?

For instance, say that you would like your inside salespeople to do more selling and less order taking. So, you plan to provide training in related selling and in selling up. You also plan to provide a module to the order system that will assist the salesperson. If the training and other efforts are successful, the good thing that will happen is that the invoice average will increase. Your reports can provide this figure.

In the example below, see how one sales manager handles this.

Jerry Frasier sat at his desk staring at the stack of notes taken in the planning meeting. Last year had been good, and senior management wanted this year to be even better. More sales and lower expenses. However, the biggest thing he had to worry about was the “more sales” part.

He pulled the year-over-year comparison report off his book shelf. He had to figure out where, in what seemed to be a mature market, he was going to find the business to meet the sales objectives. As he studied it, he noted that the big accounts — what he called core accounts — were growing a little, but the company already had most of the available business there. If they got the remainder, it still wouldn’t provide enough growth to meet the objectives.

There were some accounts on the report that bought a lot of their products from somebody, just not their company. And then there were some who ordered regularly, but even if the company got all their business, it wouldn’t make a lot of difference. Obviously, the place to concentrate was in the second group, the ones the salespeople had identified as “thrust accounts.” All he had to do was get the sales force to convert a part of these, and he could meet the sales goals. There was, however, the problem that they had discussed this at last year’s sales meeting, secured agreement from all of the salespeople, and nothing had happened. Jerry knew that he wasn’t going to get different results if the salespeople persisted in the same behaviors.

OK, if you want your people to behave differently, you needed to provide them the skills to do it successfully. He had sales training in his budget for the year. Given what he had just learned, what kind of training did they need?

He sketched out a list of the things he expected his sales force to do. It wasn’t extensive, but it broadly described their jobs. When he finished, he ranked them in terms of importance and deficiency as those factors related to what he needed to do. When he finished it, the list looked like this:

It bothered Jerry a little that almost everything ranked high in terms of importance, but that’s probably why it was on a short list. However, he could see that not everything needed the same amount of attention. The two big things were prospecting and account development — moving the thrust accounts to core account status — and working as a team with inside sales, so that they could be comfortable with spending their time developing accounts instead of babysitting.

Looking at the chart, Jerry believed that he had identified the areas properly. Now he needed to figure out what to do about them.

He didn’t have to call in a researcher to know why the salespeople spent their time on the core accounts. They said that it was to protect the account, but large accounts placed their orders through inside sales or electronically, and Jerry knew that a lot of them, maybe most of them, would rather not have as many calls from his salespeople. The real reason, he thought, was that it was much more comfortable for them to call on someone who knew them and liked them than it was to bang their way into new accounts. That was hard work, and the way they were compensated, they were working a lot harder for no increase in income.

So, based on the three reasons that he’d learned why his people didn’t do what he wanted them to do, he decided he was dealing with at least two: I won’t, and I don’t know how. That made it a training issue and a motivation issue. He knew a consultant he could bring in to develop the training. He’d done a territory management seminar at the association meeting that had made a lot of sense. Jerry made a note to call the consultant.

Now he needed to deal with the motivational issue, and this was a great time to do it. The sales force already knew that there was a new compensation plan being developed. They would look at providing a substantially higher commission on business from thrust accounts for some period of time. He made a note to talk to Frank about how to calculate that so that it held selling expenses essentially constant.

That left how to measure it. If the training and motivation were successful, they would see increased sales revenue from a defined set of accounts. That wasn’t hard to track. The important thing would be to convince everyone looking at those numbers that it wouldn’t happen quickly. It took a lot of time and effort to take business away from a good competitor. He made a note to make an immediate benchmark and to provide the growth figures to senior management at six, nine, and 12 months.

The short-term measure was sales calls on thrust accounts, and he could get that from sales reports.

So far as the outside sales/inside sales teamwork was concerned, he didn’t think that was a training issue. It was more a matter of both of them going after common goals, not a skills issue, but an attitudinal one. He’d work on a way to get them together. Certainly, they should both share in account growth. But that was a problem for another time. He had about 15 phone calls to return.

Chuck Holmes, of Corporate Strategies in Atlanta, has provided training, consulting and market research to distribution for more than 30 years. His first novel “The Sing,” a story about a black choir shaking up the racial status quo in the mid-1950s, was recently published by Deeds Publishing. Order your copy at www.chuckholmes.org.

Chuck Holmes, of Corporate Strategies in Atlanta, has provided training, consulting and market research to distribution for more than 30 years. His first novel “The Sing,” a story about a black choir shaking up the racial status quo in the mid-1950s, was recently published by Deeds Publishing. Order your copy at www.chuckholmes.org.

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2019 issue of Industrial Supply magazine. Copyright 2019, Direct Business Media.