Landing the Big Fish

Transactional Selling and the art and science of selling to big customers

by Scott Benfield

The years from 2003-2008 were a perfect storm for distribution profits. The economy was growing, commodity inflation lifted margin dollars to extremely high levels, borrowing for expansion was easy, interest rates were low, and wage inflation was kept in check by an influx of cheap labor from other parts of the world.

The years from 2003-2008 were a perfect storm for distribution profits. The economy was growing, commodity inflation lifted margin dollars to extremely high levels, borrowing for expansion was easy, interest rates were low, and wage inflation was kept in check by an influx of cheap labor from other parts of the world.

Because of this, in many markets distributors experienced some of their best returns in decades.

Today, however, the economy is retracting, commodities are deflating, and lending is tight. Even when the economy picks up, there is likely to be slow growth, high price sensitivity, and pressure on costs including labor and technology.

Many disciplines of the past won’t work or won’t work very well in this environment. Questionable initiatives include functions such as value-added selling (unless the demonstrated value lowers cost), pricing (unless pricing actions are done on a transaction size basis), and product marketing (unless the products help save labor or other costs). Distributors will need to develop efficiency, target areas of loss, and learn how to do much more with less. This will be especially true when it comes to large accounts that generate positive transaction profits. In addition, salespeople must adopt a discipline named Transaction Selling.

What is Transaction Selling and why is it needed?

Our research has concentrated on reviewing what drives operating profits. Our experience is that financial accounting with concepts such as sales, gross margins and expenses, is not sufficient to drive operating profits to superior levels. In fact, it can give very misleading information about managing profitability. Financial accounting is a time period-based discipline. In essence, financial statements are prepared for a specific period of time (month, quarter, year, etc.), with numerous transactions aggregated in the time period. The problem with aggregated transactions in a time period is that there is a general assumption that the transactions share similar costs and profit structures.

A prime example of this thinking is the practice of rewarding sales bonuses or commissions on margin dollars within a time period. For example, suppose Seller A has a base salary of $60,000 and receives a quarterly bonus on margin dollars generated in the territory. If the margin dollars were $250,000 in a quarter and the seller received 3% of margin dollars for a bonus, the bonus would be $7,500. The problem with this kind of profit measurement is that it has almost no correlation with operating profit.

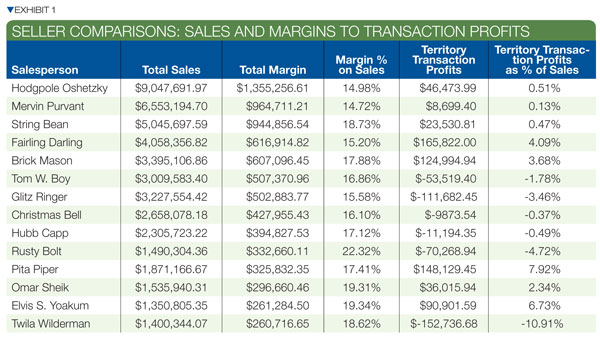

Exhibit 1 reviews Territory Profits using a discipline called Differential Costing. Differential costing uses transaction types to measure profitability by allocating operating expenses to different transactions. Different transactions have different costs. When aggregated at the territory level, 40% of sales territories typically don’t contribute to operating profit. The exhibit shows that margin dollars and sales and margin percent have no discernible effect on Transaction Profit. Some territories with high gross margin percents have negative operating profits (Rusty Bolt), and some territories with high gross margin dollars have nominal or negative transaction profits (Mervin Purvant, Tom W. Boy). In short, there is only the slightest correlation between margin dollars and operating profit growth.

Management’s desire is to reward bonuses or commissions on margin dollars to give the seller ownership in the territory and a metric from which to measure progress. The problem with margin dollars is that it is specific to a time period. Margin dollars are not connected with any operating expense at the transaction level. There is no method to gauge if a territory is profitable or not without allocating operating costs to the territory. Transaction-based allocations are unique because they represent the fundamental economic value-added of a distributor: the transaction. They also recognize that transactions either make money or they don’t and that different transactions have different costs. This led us to develop Transaction Profit Theory that says operating profit in distribution is driven by three basic measures: size of the transaction in margin dollars, type of transaction and its cost, and mix of transactions. Exhibit 2 illustrates the Three Pillars of transaction profit.

|

| Exhibit 2 |

In general, the larger the transaction in margin dollars, the more likely the order covers its processing costs. The type and cost of the transaction, as well as the mix of transactions, has significant bearing on its profitability. Common transaction types include stock (original order), stock transfer, non-stock, drop shipment, counter sale, and back-order. Typically, the majority of operating profits come from stock (original order and drop-shipments).

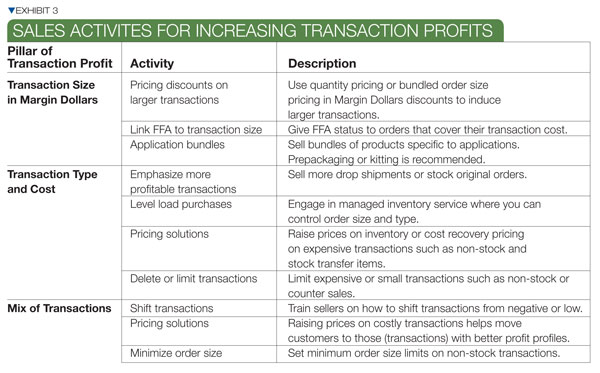

Transaction Selling is the discipline of using Transaction Profit Theory to drive sales activities that grow operating profits. Exhibit 3 breaks down the Pillars of Transaction Profit into activities that help in growing operating income.

The chart divides each Pillar into key activities and briefly describes the activity. Under increasing transaction size, the first recommendation is to base pricing on larger transactions, including quantity break discounts and bundled order size pricing. To perform bundled order size pricing consistently, it’s best to develop discounts from list by order size. In essence, a 35% discount for a list-price order of $700 and a 25% discount for a $500 size order. The firm will need a proprietary list-price logic to accomplish this. However, pricing can have great influence in increasing order size. Also, if possible, I recommend determining the breakeven order size for a stock original order and setting the FFA policy at this level. In essence, freight is “free” as long as the order is above a minimum value. Too often, distributors deliver a $25 order FFA when the shipment cost is $25. Finally, it can be effective to bundle products in application kits with a bundled price. In many instances, you can’t substitute a part or piece without changing other items. Bundling these items into one price is a great way to add size to the transaction.

The chart divides each Pillar into key activities and briefly describes the activity. Under increasing transaction size, the first recommendation is to base pricing on larger transactions, including quantity break discounts and bundled order size pricing. To perform bundled order size pricing consistently, it’s best to develop discounts from list by order size. In essence, a 35% discount for a list-price order of $700 and a 25% discount for a $500 size order. The firm will need a proprietary list-price logic to accomplish this. However, pricing can have great influence in increasing order size. Also, if possible, I recommend determining the breakeven order size for a stock original order and setting the FFA policy at this level. In essence, freight is “free” as long as the order is above a minimum value. Too often, distributors deliver a $25 order FFA when the shipment cost is $25. Finally, it can be effective to bundle products in application kits with a bundled price. In many instances, you can’t substitute a part or piece without changing other items. Bundling these items into one price is a great way to add size to the transaction.

Under transaction size and cost activities, it often helps to train sellers on how to look at the current mix of transactions and move the business to a more profitable transaction type. In one industry, a customer accepted drop shipments at a lower price than receiving shipments of stock orders from satellite branches. The better price was offset by the larger order size and the positive contributions of less costly but much more profitable drop shipments.

Inventory management services can control transaction size by increasing the number of days-on-hand of inventory and smoothing out or level-loading demand so that transactions are more sizable and maximize order fulfillment labor.

Pricing can also help drive transaction profits. In some cases, transactions with low or negative profitability can yield higher margins, or cost recovery for expensive operations can offset potential losses. Finally, some transactions can be limited or deleted entirely. One fastener distributor found that only a small group of counter sales generated a positive transaction profit. The company ceased counter sales with the exception of a few key customers that received a pick up option at the local branch.

Changing the mix of transactions can have a dramatic increase on profits. For example, one jan./san. distributor served a multi-million dollar account by shipping orders to 300 stores nationwide. We totaled the volume and types of products sold and worked with our client to sell the products direct to a central warehouse. The customer received much better prices and the wholesaler turned a transaction negative account into a transaction positive contributor.

Transaction selling requires more than simply reminding sellers to sell larger orders or sell more profitable transactions. It requires a well-documented plan, with supporting analytics on where to find opportunities. Only then can you develop a sales plan that increases transaction

profits. It is possible to mitigate loss on many negative transactions and free up capacity to service larger customers. This avoids increasing headcount and, often, wholesalers can take a low-cost service platform to the street as a lower price.

Our research finds that 40% of customers make up 136% of operating profits. In addition, three transactions (stock original order, stock transfer and drop shipment) average 70% of shipments but produce 130% of operating profits.

Transaction-based costing can pinpoint areas of loss including customers, sellers and transaction types. Once the losses are identified, they can be mitigated or reversed, enabling distributors to server larger customers more profitably at better prices.

Scott Benfield is a consultant for industrial manufacturers and distributors. He can be reached at bnfldgp@aol.com or (630) 428-9311. View Scott’s white paper on Transaction Management at www.benfieldconsulting.com.

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2009 edition of Industrial Supply magazine. Copyright 2009, Direct Business Media, LLC.