The Value Decade

Serving the ecnomic buyer

By Scott Benfield

A primary problem with the bundled basic service model of distribution is that it is inefficient. Many wholesalers doubt this statement, as most durable goods industries average a 2.5% return on sales (ROS) and don’t see how the industry could be any more efficient with the existing margins. However, our work in using a transaction-based costing logic for cost allocations finds that 40% of customers cover their weighted average cost of capital, while 60% of customers don’t cover their capital costs and literally destroy financial value. We also refer to the first article in the series, where Profit Planning Group has found for the past two decades that wholesalers have not reduced their payroll costs as a percent of their sales volume. Click here to read the article, “The Value Decade.”

With basic services, there are numerous ways of tailoring pricing, delivery, invoicing, collection and inventory needs of individual customers. Sellers, compensated on margin dollars, have every motivation to customize the service platform by account. For instance, if a distributor has 10 outside sellers with 75 assigned accounts who average 250 invoices per year and each seller customizes an average of three services per account, the possible permutations of service variation are (10 x 75 x 250 x 3) or 562,500. Most distributors don’t realize that the customization of basic services by account adds tremendous complexity and cost to the operating platform.

The customization of basic services is a key contributing factor for the imbalance in a minority of accounts covering their capital costs. Many distributors provide full service to the majority of accounts, including assigning an outside sales representative and inside sales order management. The inside and outside sales resource is the most expensive part of operating expenses and many accounts that receive sales assistance can’t afford it or don’t necessarily want it.

Our work in evaluating service platforms, including sales-led sevice customization, finds that many customers don’t value services the same and, if given a price reduction for traditional services not provided by the distributor, would choose a reduced price.

Hence, there is room for an operating model that is dedicated to delivering a low-cost service at an attractive price. In essence, a distributor that reduces variation on services and substitutes expensive services such as outside sales with e-commerce can greatly reduce operating expenses and pass part of the reduction on to the customer. Therefore, an operating model with narrowly defined service(s) and limited service variation that targets customers who are satisfied with internalizing or foregoing customized or extra services, has a good chance of success if it can deliver an attractive price to the economic buyer.

Where the Economic Buyer is Likely to Live

Where the Economic Buyer is Likely to Live

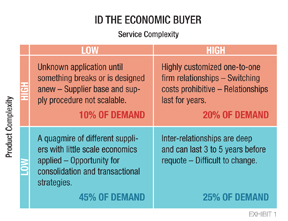

The economic buyer, typically, has low complexity of product and service needs. In Exhibit 1, we have listed Product Complexity on the Y axis and Service Complexity on the X axis along the qualifiers of High and Low for each axis. For instance, the Northwest Quadrant of High Product Complexity and Low Service Complexity is often found in manufacturing job shops or labs where detailed design, customer manufacturing or research work is done. While the customers may be small in annual volume, they typically have larger order sizes due to the complexity of products purchased. We estimate their potential at 10% of overall demand. The High-High or Northeast Quadrant involves larger customers who need constant attention and are Enterprise relationships, and the Southeast Quadrant, with low product complexity and high service complexity, are often Integrated Supply relationships. Economic buyers are found in the Southwest Quadrant. They are candidates for focused, streamlined wholesale models featuring limited service variation and an attractive price. They represent, from our field work, nearly half of all demand.

The problem with the Low-Low quadrant is that many distributors over-serve the customer base with service variation, constant sales effort and ordering assistance. This over-servicing is aided by margin dollar compensation, inaccurate or non-existent service cost allocations, and a sales orientation that assumes greater call volume will equal greater sales penetration. During the last decade and with the arrival of e-commerce, global sourcing and a detailed understanding of transaction costs, there has appeared a type of distribution firm named Transactional.

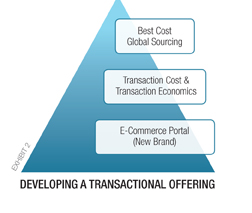

Transactional distributors source the lowest global cost of acceptable quality for buy side advantages of 20% to 30% over established brands. They use e-commerce as an order portal, offer very little sales support and have accurate cost allocation models that help in aligning service support and pricing with the customer’s ability to pay. We consider the recent announcement of AmazonSupply to be a transactional offering. Transactional distributors have few branches and prefer larger warehouses in metropolitan areas. Our benchmarking of transactional distributors finds they can typically reduce price 20% to 30% less than existing bundled service distribution models and have ROS of 3x to 5x that of traditional distributors. This performance parallels the performance of stripped down cost e-commerce models in hard-goods retailing that typically reduce price by 20% or more over their brick and mortar competitors. The building blocks of the transactional distributor are seen in Exhibit 2.

Transactional distributors source the lowest global cost of acceptable quality for buy side advantages of 20% to 30% over established brands. They use e-commerce as an order portal, offer very little sales support and have accurate cost allocation models that help in aligning service support and pricing with the customer’s ability to pay. We consider the recent announcement of AmazonSupply to be a transactional offering. Transactional distributors have few branches and prefer larger warehouses in metropolitan areas. Our benchmarking of transactional distributors finds they can typically reduce price 20% to 30% less than existing bundled service distribution models and have ROS of 3x to 5x that of traditional distributors. This performance parallels the performance of stripped down cost e-commerce models in hard-goods retailing that typically reduce price by 20% or more over their brick and mortar competitors. The building blocks of the transactional distributor are seen in Exhibit 2.

Transactional distributors are on the rise as customers are more value conscious in a slow-growth economy and the use of mobile devices to check price and availability is becoming more mainstream. Typically, transactional distributors carry the 20/80 inventory items and tie transaction size to a freight minimum. For instance, in building a recent transactional offering for a client, we found that a minimum stock order of $250 was required before freight costs were covered and we tied FFA to a breakeven transaction size. Also, transactional distributors can discount by transaction size and accurately estimate the operating profit contribution of an order type.

Transactional distributors can be highly disruptive to traditional distribution. They often target leading customers and larger order sizes. If successful, they leave traditional distributors selling C&D items and special sourcing non-stock orders which, in most instances, puts the traditional firm on the ropes. We have done work in industries where transactional distributors have literally placed their competition in the red. As the second decade of the New Millenium matures, our expectation is that transactional distribution will become more commonplace. Many traditional distributors will try and combat them with selective, reduced pricing but this typically is an ineffective response. Unless the traditional distributor reduces operating costs while understanding their fulfillment costs

by transaction and has low-cost (global sourced) private brands, they will not be able to make a transactional strategy work.

The culture of transactional distributors is a great price for limited service. Many full-service distributors can’t overcome the cultural barriers of marketing a limited service offering; the desire to promise customers unique services is too strong and this destroys the low-cost/simplified service offering. Hence, we expect many traditional distributors to attempt a transactional model but many will fail as they underestimate the time required, information complexity and work that goes into establishing global supply chains. We have recently witnessed two failed transactional model attempts in the building products and HVAC industries where executive management simply tried to limit service and reduce price on top of the existing culture. The employees were too ingrained in the full service bundled model where customization of services was common. They failed miserably in an environment where they could not give their long-time customers variations on product and service choices.

In the Value Decade, a legitimate and growing response to service economic buyers will be identifying segments with low service and low product complexity. From there, the combination of e-commerce ordering and solicitation, global best-cost supply chains, and use of transaction costs and economics creates the opportunity for transactional distributors where price reductions of 20% to 30% are not uncommon. Our advice for traditional distributors is to develop global supply sources and engage accurate cost allocation models that give an understanding of fulfillment costs of different transaction types and how to reduce fulfillment costs by increasing transaction size, using low-cost private label products and limiting discretionary services. Otherwise, if a transactional distributor comes calling on economic buyers, the battle was lost by the traditional distributor well before the price reaches the marketplace.

Scott Benfield is a consultant for B2B channels and can be reached at (630) 428-9311 or scott@benfieldconsulting.com. The following series is taken from his new book “Building Value: Driving Wholesaler Returns Through Strategic and Tactical Investment,” which can be ordered at www.benfieldconsulting.com.

This article originally appeared in the Sept./Oct. 2012 issue of Industrial Supply magazine. Copyright 2012, Direct Business Media.